What sociology and philosophy teach us about political Albania.

Since my background comes from Social Sciences, and specifically from Sociology, I could not exclude this analysis to understand what is happening today in our country. There is an unwritten law of politics that philosophy and sociology have long understood, but that Albanian society still refuses to fully accept: power is divided to rule, but united to survive.

Vilfredo Pareto was not talking about individuals, but about elites and Albania today is an open laboratory of this law.

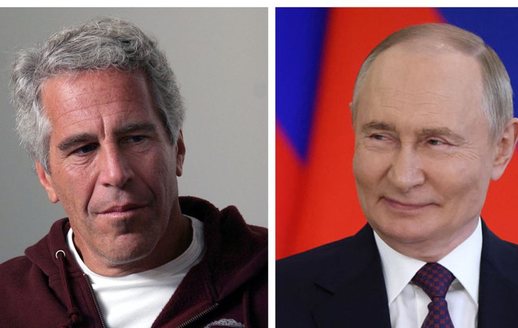

On the surface, Albanian politics appears divided, polarized, mired in perpetual conflict. Berisha and Rama appear as existential opponents, as two worlds that never meet. But this division only works as long as politics remains a game of power. The moment SPAK enters the scene, the dividing lines begin to fade and a common feeling that unites everyone emerges: fear.

Political sociology teaches us that elites are rarely overthrown by one another. They are replaced, recycled, and rotated within the same system. What really shocks them is not the loss of power, but the loss of immunity. For the first time in decades, Albanian politics is confronted with an institution that does not negotiate with the narrative, but demands accountability. SPAK is not simply a justice structure; for the political class, it is an existential threat.

Hannah Arendt clearly states: power is not afraid of the opposition, but of judgment, because judgment takes power out of propaganda and into the territory of personal responsibility. This is precisely where Albanian politics feels vulnerable. In the face of SPAK, political actors are no longer rulers, but subjects of investigation, and this is for them a reversal of the order they have known.

Carl Schmitt would call this a “situation of exception”: the moment when politics ceases to be ideology and becomes a survival instinct. When the adversary is no longer the “political other” but criminal justice, major conflicts are suspended and a silent solidarity arises. Not public agreement, but a psychological and strategic rapprochement, dictated by fear.

This explains why Berisha and Rama can clash fiercely for votes, for history and for power, but in the face of SPAK their language becomes closer, their reactions begin to resemble each other and their attacks on justice become synchronized, sometimes direct, sometimes disguised. The message is the same: justice yes, but not the one that affects us.

Filozofia dhe sociologjia nuk flasin këtu për dy individë, por për një klasë politike që e percepton SPAK-un jo si instrument të shtetit, por si rrezik personal. Siç do të thoshte Pareto, elitat ndahen për të sunduar shoqërinë, por bashkohen për të mos u gjykuar prej saj dhe sot, ajo që i bashkon më fort se çdo ideologji është frika nga drejtësia.

Problemi i Shqipërisë nuk është konflikti politik, por një sistem që e pranon konfliktin si spektakël dhe e sheh drejtësinë si armik. Një sistem i mësuar të sundojë pa u gjykuar dhe që sot, për herë të parë, po ndien pasigurinë e llogaridhënies. SPAK-u nuk është më një “problem ligjor” për kundërshtarin; është pasqyrë ku pushteti sheh armikun e vetëm që nuk mund ta blejë, nuk mund ta manipulojë dhe nuk mund ta anashkalojë.

Berisha dhe Rama mund të vazhdojnë teatrin e përplasjes politike, por pas maskave, po afrohen në heshtje për të mbrojtur privilegjet e tyre. Për herë të parë, politika shqiptare nuk po mendon për votuesit, programet apo ideologjinë, ajo po mendon për veten dhe trashgiminë. Po sheh rrezikun nga SPAK-u dhe ky rrezik është i vetmi që realisht mund ta shkundë nga karriget e pushtetit politik-ekonomik që i kanë mbajtur në këmbë për dekada.

Se vjen një moment që drejtësia nuk pyet për fraksione, nuk dallon parti dhe nuk njeh miq politikë. Ajo godet aty ku duhet dhe pikërisht kjo është frika që sot i bashkon të gjithë.

Happening now...

ideas

Ilir Meta, this gypsy of Edi Rama!

How to govern the country and lead the opposition... for yourself!

top

Alfa recipes

TRENDING

services

- POLICE129

- STREET POLICE126

- AMBULANCE112

- FIREFIGHTER128