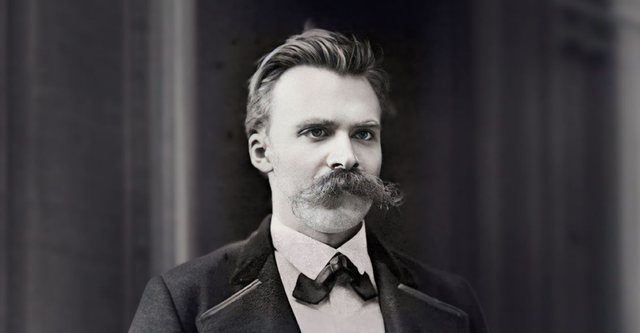

How Nietzsche Deconstructed Good and Evil in "The Genealogy of Morality"

We build our lives on the basis of morality, but have we ever stopped to ask where it comes from?

In “The Genealogy of Morality,” Nietzsche analyzes what we commonly consider good and evil, with the goal of dismantling these concepts. This revolutionary work, first published in 1887, rejects the idea that moral values are given from above or that they can be derived from reason. Instead, Nietzsche argues that they arise from power conflicts, from the ways in which people are psychologically manipulated into accepting them, and from deep feelings of resentment and resentment.

Let's explore them in turn.

From the question "What is right?" to "Where does morality come from?"

Philosophers before Nietzsche had tried to define what morality should be—whether that of reason (according to Kant) or of utility (according to Bentham and Mill). But Nietzsche turned the question upside down: he no longer asked what is right, but where morality itself comes from.

According to him, values are not universal or absolute. They are products of power relations, psychology, and history. This is Nietzsche's genealogical stance – he observes how morality evolves over time, without assuming the existence of an eternal morality.

Just as Darwin saw the evolution of species to survive, Nietzsche believed that values also evolve within social and historical contexts. The ancient values of warrior cultures – strength, pride, bravery – were cast aside by religious values that promoted humility, submission, and guilt.

Two moralities: that of the Masters and that of the Slaves

Nietzsche's radical discovery was that morality is not a gift from God or reason – it is a creation of the powerful to serve their own interests.

So our values today may not be as “natural” or “good” as we think. And if humans invent morality, do we have the right to challenge and rewrite it?

In the book, Nietzsche divides morality into two camps: the Morality of Masters and the Morality of Slaves – born of two different types of people.

The morality of the Gentlemen comes from the great, the strong, and the powerful – the aristocracy, the rulers, the warriors. For them, “good” was what was associated with strength, courage, health, power. Weakness and failure were “bad.” Think of Greek heroes like Achilles – ambitious, proud, invincible.

The morality of the Slaves, on the contrary, was born of the weak, the oppressed, the bitter. They inverted morality: weakness became virtue, suffering became holiness, submission became goodness.

Humility, gentleness, and obedience were elevated to a pedestal – values that suited the powerless, but which limited human energy.

Christianity – the final victory of slave morality

Niçja e pa Krishterimin si triumfin përfundimtar të moralit të skllevërve. Krenaria u kthye në mëkat, fuqia në mizori, vuajtja në shpëtim. Në vend që të nderoheshin heronjtë, morali nisi të nderonte martirët.

Dhe pyetja që ai ngre mbetet therëse: A janë vlerat tona vërtet tonat, apo i kemi trashëguar verbërisht nga një moral që synon të na dobësojë?

Mëria e brendshme e të dobtëve

Niçja e quajti këtë ndjenjë “ressentiment” – një mëri e thellë, jo thjesht xhelozi apo zemërim, por urrejtje e fshehtë ndaj fuqisë, që i shtyn të dobëtit të shpikin moralin e vet. Ata nuk pranojnë vendin e tyre – e përmbysin sistemin: e bëjnë mjerimin virtyt dhe fuqinë mëkat.

Në Romën e lashtë, virtyti ishte forca, heroizmi dhe pushtimi. Por me përhapjen e Krishterimit, këto u shpallën të këqija: krenaria u bë ves, përulësia u bë virtyt, dhe martirizimi u shenjtërua. Morali nuk krijohej më nga të fuqishmit, por nga ata që e urrenin pushtetin.

Aktualiteti i Niçes: nga politika te kultura e viktimës

Kjo analizë nuk i përket vetëm historisë. Niçja do të thoshte se edhe sot, luftrat ideologjike, kulturat e viktimizimit dhe konfliktet politike ndjekin të njëjtat dinamika.

Shumë lëvizje moderne e ndërtojnë “mirësinë” e tyre mbi hidhërimin ndaj pushtetit, duke e kthyer dobësinë në një formë të re force.

Kështu, Niçja pyet: A po i ndërtojmë vlerat tona mbi fuqinë, apo po e lëmë hidhërimin të na verbojë?

Faji dhe “ndërgjegjja e keqe”

A të ka ndodhur ndonjëherë të ndihesh fajtor për diçka, edhe pse s’ke bërë asgjë? Niçja thotë se kjo “ndërgjegje e keqe” nuk është natyrore – është e mbjellë nga shoqëria.

Në fillimet e njerëzimit, morali nuk kishte lidhje me fajin e brendshëm, por me shpagimin. Nëse i bëje dëm dikujt, nuk ndiheshe fajtor – paguaje dëmshpërblim. Por me kalimin e kohës, dënimi u kthye nga jashtë në brenda. Shoqëria filloi të të kontrollonte përmes vetëdijes. Ligjet, feja, normat shoqërore u bënë pjesë e brendshme e njeriut.

Krishterimi e thelloi këtë: tani njeriu nuk duhej vetëm të paguante, por të ndjente faj shpirtëror, si mëkatar që duhej të vuante për t’u pastruar. Faji u kthye në instrument kontrolli.

Edhe Frojdi më vonë e përshkroi diçka të ngjashme me konceptin e tij të “super-egos” – një zë i brendshëm që na ndalon, që na bën të ndjejmë turp e faj.

Por Niçja pyet: A është ndjenja e fajit vërtet morale, apo thjesht një mënyrë për të na mbajtur të nënshtruar?

“Forca e vullnetit”: alternativa e Niçes

Sipas Niçes, moralet ekzistuese shpesh promovojnë vuajtjen, sakrificën dhe mohimin e kënaqësisë – ai i quajti këto “vlera asketike.” Nga murgjit fetarë që kërkonin pastërti përmes agjërimit, te profesionistët modernë që besojnë se ndjenjat janë pengesë për arsyen – të gjithë ndjekin të njëjtin ideal: nënshtrimin e jetës.

Por Niçja akuzon këta “predikues të dhimbjes” se na kanë mashtruar të gjithëve.

Këto vlera nuk e përmirësojnë jetën – e bëjnë njeriun të sëmurë shpirtërisht dhe të ndarë nga natyra e tij krijuese.

Instead, he proposes willpower – the power to create, to grow, to transcend oneself.

Not to suppress desires, but to transform them into constructive energy.

This remains relevant today. From extreme diets, to minimalist lifestyles, or ideologies that glorify “suffering for a cause,” Nietzsche would ask: Are we limiting ourselves because we feel empowered to do so, or are we following orders that impose this pain on us?

"The Genealogy of Morality" is not just a book of philosophy—it's a shake-up of the foundations of morality. It changed the way we think about good and evil.

Existentialist and postmodernist philosophers were inspired by him: Foucault used the genealogical approach to analyze how power functions in institutions; Deleuze showed how morality shapes the individual; Derrida asked whether there is any immutable moral truth.

In psychology, Freud and Nietzsche saw guilt as an internal product of society, while Jung saw it as an opportunity for self-knowledge – a process he called “individuation”.

But Nietzsche's ideas remain controversial. Some believe they lead to moral relativism - that there is no longer any right or wrong.

Others fear that it can produce extreme selfishness, where one thinks only of oneself. Yet his books are still read because they raise the most fundamental question: Why do we trust values just because they are old?

Nietzsche shows us that ancient ideas about good and evil arose from power and life-affirmation, but were replaced by a morality that glorifies guilt and control.

We have inherited this way of thinking, often without realizing it. Instead of encouraging us to develop, morality often commands us to remain obedient and restrained.

So, Nietzsche's final question is this: Are we truly free people, or are we still taught to fear our potential – like an animal that is forbidden to do its tricks because every time it tries, someone scares it? /bota.al

Happening now...

ideas

top

Alfa recipes

TRENDING

services

- POLICE129

- STREET POLICE126

- AMBULANCE112

- FIREFIGHTER128