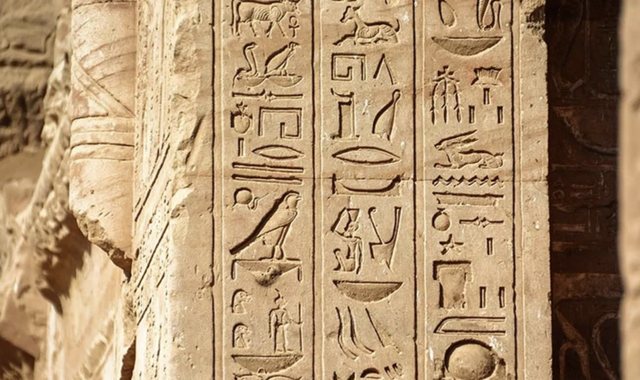

Ancient Egyptian Alphabet: What are Hieroglyphs?

Ancient Egypt has left us images of towering pyramids, dusty mummies, and walls covered in hieroglyphics, symbols depicting people, animals, and strange-looking objects. These ancient symbols – the ancient Egyptian alphabet – bear little resemblance to the Latin alphabet we know today.

The meaning of Egyptian hieroglyphs remained somewhat of a mystery until the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1798, after which French scholar Jean-François Champollion was able to decipher the mysterious language. But where did one of the world's most iconic and oldest forms of writing originate, and how do we understand it? And what is the origin of hieroglyphs?

Since 4000 BC, people have used drawn symbols to communicate. These symbols, carved on clay pots or tablets found along the banks of the Nile in tombs belonging to the elite, date back to the time of a predynastic ruler named Naqada or “Scorpio I,” and were among the earliest forms of writing in Egypt.

However, Egypt was not the first country to communicate through writing. Mesopotamia already had a long history of using symbols dating back to 8000 BC. While historians still debate whether or not the Egyptians got the idea for developing an alphabet from their Mesopotamian neighbors, hieroglyphs are distinctly Egyptian, and reflect the flora, fauna, and images of Egyptian life.

By the beginning of the Old and Middle Kingdoms of Egypt from 2500 BC, the number of hieroglyphs was about 800. When the Greeks and Romans arrived in Egypt, more than 5,000 hieroglyphs were in use. But how do hieroglyphs work? In hieroglyphs, there are 3 main types of glyphs.

First are phonetic glyphs, which include single characters that function like the letters of the English alphabet. Second are logographs, written symbols that represent a word, much like the letters of the Chinese alphabet. And third were taxograms, which can change meaning when combined with other glyphs.

As more and more Egyptians began to use hieroglyphs, two types of writing emerged: hieratic (priestly) and demotic (popular). Carving hieroglyphs on stone was a complicated and expensive process. Thus, a need arose for an easier cursive script.

Hieratic hieroglyphs were best suited for writing on papyrus made of reed and ink. They were used primarily for religious writing by Egyptian priests, as the Greek word that gave the alphabet its name; hieroglyphikos means “carving of the sacred word. ”

Shkrimi demotik u zhvillua rreth vitit 800 Para Krishtit, për t’u përdorur në dokumente të tjera ose shkrimin e letrave. Ai u përdor për 1000 vjet, dhe shkruhej dhe lexohej nga e djathta në të majtë si arabishtja, ndryshe nga hieroglifët e mëparshëm që nuk kishin hapësira midis tyre dhe mund të lexoheshin nga lart poshtë.

Prandaj, kuptimi i kontekstit të hieroglifeve ishte shumë i rëndësishëm. Hieroglifët ishin ende në përdorim nën sundimin pers gjatë shekujve VI-V Para Krishtit, dhe pas pushtimit të Egjiptit nga Aleksandri i Madh. Studiuesit mendojnë se gjatë periudhës greke dhe romake, hieroglifet përdoreshin nga egjiptianët, si një përpjekje për të dalluar egjiptianët “e vërtetë” nga pushtuesit e tyre.

Edhe pse, kjo mund të ketë qenë më shumë një zgjedhje e vetë pushtuesve grekë dhe romakë, për të mos e mësuar gjuhën egjiptiane. Gjithsesi, shumë grekë dhe romakë mendonin se hieroglifët bartnin njohuri të fshehura, madje magjike, për shkak të përdorimit të tyre të vazhdueshëm në praktikën fetare egjiptiane.

Por gjatë shekullit IV Pas Krishtit, pak egjiptianë ishin të aftë që t’i lexonin hieroglifet. Perandori bizantin Theodosi I, i mbylli të gjithë tempujt jo të krishterë në vitin 391, një akt që solli edhe fundin e përdorimit të hieroglifeve në godinat monumentale. Studiuesit mesjetarë arabë Dhul-Nun El-Misri dhe Ibn Uashshija, bënë përpjekje për të përkthyer simbolet e atëhershme të huaja.

Por përparimi i tyre bazohej në besimin e gabuar se hieroglifet përfaqësonin idetë dhe jo tingujt e folur. Përparimi në deshifrimin e hieroglifeve, ndodhi pas një pushtim tjetër të Egjiptit, këtë herë nga Napoleon Bonaparti. Forcat e Perandorit, një ushtri e madhe që kishte me vete shkencëtarë dhe ekspertë të kulturës, zbarkuan në Aleksandri në korrikun e vitit 1798.

Një pllakë guri, e gdhendur me glife, u zbulua si pjesë e strukturës në fortesën Zhylien, një kamp i pushtuar nga francezët pranë qytetit të Rozetës. Sipërfaqja e gurit mbulohet nga 3 versione të një dekreti të lëshuar në Memfis nga mbreti egjiptian Ptoleme V Epifanes në vitin 196 Para Krishtit.

Tekstet në pjesën e sipërme dhe në mes janë me shkrime hieroglife dhe demotike të egjiptianishtes së lashtë, ndërsa pjesa e poshtme është shkruar në greqishten e vjetër. Gjatë viteve 1822-1824, gjuhëtari francez Zhan-Fransua Shampoljo zbuloi se 3 versionet ndryshojnë vetëm pak nga njëri-tjeri. Guri i Rozetës (që ndodhet sot në Muzeun Britanik) u bë çelësi për deshifrimin e shkrimeve egjiptiane. Pavarësisht zbulimit të tij, sot interpretimi i hieroglifeve mbetet një sfidë edhe për egjiptologët me përvojë./Bota.al

Happening now...

America may withdraw from Europe, but not from SPAK

ideas

top

Alfa recipes

TRENDING

services

- POLICE129

- STREET POLICE126

- AMBULANCE112

- FIREFIGHTER128